Modern Anisospondyls can be placed into one of three major categories. There are the Brachiostomata, a group which was apparently very diverse in Eryobis' her past but is now only represented by a handful of species. There are the Cryptognatha, the Anisospondyls that evolved a second set of jaws derived from their palates and tongue bones and the group that by far the most modern Anispondyls fall into.

And then there the Trapezostomata. These creatures are most easily recognized by a feature seen in no other Anisospondyl living or dead: an elongated bony plate below the mouth called the trapezium.

It is theorized that they evolved this feature to combat the ever existing issue caused by having horizontally opening mouths, food falling out. The trapezium prevents this. To accompany this, many Trapezesotomes also have fleshly, often muscular lips and cheeks.

Trapezostomes are likely just as old as, if not even older of a clade than the Cryptognaths. Genetic evidence suggests that the two lineages had already split around 160 million years ago in the Swifterbantian stage of the Bobossic period. The two main branches, as well as likely a few more, of Trapezostomata were already well established by the Jerounian and Kikilian stages, as is shown by a rather derived member of Liomedactylomorpha having been found in the Reinaut Formation dated to the end of the Bobossic.

In modern times, we can place Trapezostomes into one of two groups, the Liomedactylomorpha and the Strotopalates. The molecular clock suggests these groups differentiated between 145 and 130 million years ago and thus must have survived the cataclysm known as the World Scarring at the end of the Bobossic independently.

Of these two groups, the Strotopalates are typically regarded as the more primitive of the two.

Strotopalates are most easily distinguishable by their jaw anatomy. The seem to have lost their palatine teeth very early in their history and evolved to have a completely closed palate that bears a striking resemblance to those of placental mammals. Their dentary likewise has also been sealed off. This likely evolved to grant early Strotopalates a stronger bite.

Their land based representatives are relatively few in number and are reptilian in appearance, usually being scaly and ectothermic. The most basal members, the Tardosaurids, are medium sized slow moving herbivores that inhabit a number of small islands in the central and southern regions of Rubiëra. The Novalacertoids are bit more diverse and widespread, being found in virtually every corner of the Rubiëran archipelago. They are usually small with very elongated, almost serpentine bodies, consequently they mostly feed on burrowing arthropods and annelids.

The Hastamentids are perhaps some of the most recognizable Trapezostomes alive. Some of their species can stand up to 1.5 meters at the shoulder and all can be quickly recognized by the long spear like trapezium sticking out far beyond their jaws. This peculiar trapezium is, quite obviously, used to spear prey. Most Hastamentids are semi-aquatic and often hunt by standing by the waters edge and impale aquatic prey that comes to close.

Their visendal arms are permanently held off the ground and are mainly used to manipulate food speared up on their trapezium.

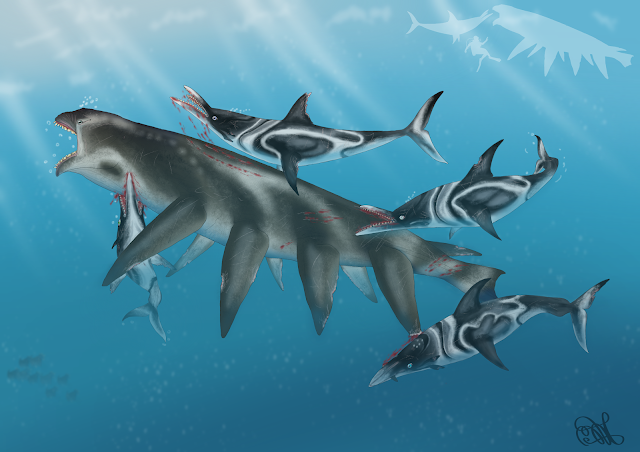

But there is another superfamily that belongs to Strotopalates that strayed quite far from their other kin. These are the Fermourodonts, fully marine creatures that are neither scaly nor ectothermic like other Strotopalates. One of their most defining traits are their jaws and skulls. Anisospondyl skulls in general are odd looking and appear twisted and disfigured compared to Tetrapod and Arachnopod skulls, but Fermourodonts take this a step further. Their caecal spircales have migrated to the visendal side and as a result warped the entire skull. Fermourodonts thus possess the unique ability to open their jaws at wide and odd angles that, in combination with the trapezium, results in them having a three part jaw. This allows them to chop and slice their prey in ways that no other animal can.

It is unclear where Fermourdonts came from since they have no close terrestrial relatives anywhere. Because of this, there are some that suggest Fermourodonts might have evolved somewhere other than Rubiëra, where all other Strotopalates can be found, but until some fossils are discovered, we cannot know. In modern times, we see two distinct kinds of Fermourodonts, the Palaionychids that somewhat resemble the prehistoric Metriorhynchids of Earth and the Fermourodontoids, the infamous "zipper dolphins" or ritsuara's of Eryobis.

Both of these groups are fully aquatic, although Palaionychids still do possess some functional digits and claws, these are mainly used to help them navigate through reefs, crevices and vegetation. Another unique trait that all Fermourodonts possess is what can best be described as "electrical whiskers". Their jaws are covered in rows small of electric organs that create a small electromagnetic field around the snout. This allows them to perceive living things without needing to see them. This adaptation is also a reason why Fermourodonts seem to despite humans. Our electrical equipment and ROVs seem to agitate them to the point where some will actively attack and destroy our devices whenever they encounter us.

It is a shame really, because Fermourodonts have proven to be among the most intelligent creatures on Eryobis, yet we evidently cannot examine them up close in their natural habitat.

Liomedactylomorpha are regarded as more advanved compared to Strotopalates. One of the reasons for this is the fact that Liomedactylomorphs symmetrized the toes on their front limbs. While several other groups like Eusymmetrodactyl and Parasymmetrodactyl also symmetrized their toes by reducing a toe of their lacrimal limbs, Liomedactylomorphs instead fused the 3rd and 4th digits into one.

Another is the removal of the ancestral "fish nostrils" from the jaws and having those be replaced by new olfactory organs derived from glands near their eyes. These drape down from the eyes and end around the corner of the mouth between the mandibles and the trapezium.

Without the exception of the Trapezosauridae, all Liomedactylomorphs fall into Liomedactylae. Likewise, all except the former all endothermic creatures possess some kind of fur covering. Liomedactyls possess prominent spiracle structures made out of bony rings and cartilage. These resemble the spiracle structures of Eusymmetrodactyls in the fact that they are also covered in hard keratin, but unlike those, the spiracle structures of Liomedactyls split into two separate tubes akin to the fleshy spiracle structures of some Effingodactyls.

Uniquely, Liomedactyls have evolved to use these largely hollow tubes to detect sound and as such, usually have several disc like shaped and pressure points spread over their headgear.

The most basal members, the Trochotheroids, are Mustelid like omnivores that typically have long bodies with relatively short legs.

Triprotodontia

Other Liomedactyls seem to be largely divisible into three major lineages.

The first of these is the branch that leads up to the Triprotodontia. All members of this branch can be identified by the orientation of their toes on the hind legs, with the first, second and third digits being mainly used for walking while the fourth and fifth digits are reduced and often vestigial. Odd looking creatures like herbivorous Kormerpetontids and the rat/ shrew like Projunctinariids belong at the base of this branch.

The latter represent a transitional form between more basal Liomedactyls and the advanced Triprotodonts. These have a number of unique features, like their spiracular structures that feature large auricule spheres at the back of the head and tube openings that always face out- or backwards. They also possess the ability to open their jaws at an odd angle, giving them an almost three part jaw, although it is nowhere near as developed as those seen in Fermourodonts.

But perhaps the most unique feature of Triprotodonts is the fact that they have fused their caecal spiracle opening with their olfactory organs and moved this newly evolved "nose" to the very front of the trapezium. This makes them look as if they have an inverted mammal snout and is an adaptation seen in no other group of Anisospondyls.

Triprotodonts are the most successful and widespread clade of non-flighted terrestrial Anisospondyls ever. These rodent like creatues are present on every major landmass except the continent of Hatèmica and often dominate the niches of small sized herbi- and omnivores. They are divided into three groups mostly based on where they can be found.

On the continents of Tlèëa, Guralta and Lachoba, we can find the Boreoglires that were named because they took the northern route to spread across the continents.

The other two groups are generally considered to be more closely related to each other than either is to Boreoglires. The Rubioglires are the group of Triprotodonts that mostly restricted to the Rubiëran archipelago, while the Austroglires are almost exclusively found on the continent of Miesjeta.

Diplaulotes

Besides the Triprotodontia, there are two other, often more noticeable lineages of Liomedactyls.

Both of these have features that easily set them apart from any other Anisospondyl family dead or alive.

The clade known as the Diplaulotes possess some of the most charismatic headgear of any animal on Eryobis. At some point in their evolution, a mutation occurred that caused them to grow a spiracular structure not just on the visendal spiracle, but on the caecal side as well, giving them their iconic quadruple tubed look.

The most basal Diplaulotes are the Tetramyteiids, a family of civet like creatures that are quite similar to the Trochotheroids in appearance and lifestyle.

The other Diplaulote groups are united by a few characteristics in their foot anatomy such as the sideways orientation of their hands on their front feet and the loss of the fifth digit on the hind-limbs.

While nearly all members of this group are devoted herbivores and occasional omnivores, they do contain one family of hypercarnivores, the Machairoplatids. These feline looking predators have evolved a large sharp spike on the edge of their trapezium which they use to kill, much like the saberteeth of various prehistoric carnivores from Earth. Machairoplatids always hold their caecal limbs, which are set further towards the middle than the visendal limbs, permanently off the ground. These free arms have opposable fingers that sport large claws for restraining prey before they can deploy their sabers as well as for carrying their offspring.

The other "higher" Diplaulotes are nearly all herbivores. Some of these, like the Grothiacheirids have evolved one pair of their front limbs into club like appendages. These are made out of their modified foot bones and are lined by their stud like hooves.

The Liotelares are typically more stocky in build that other Diplaulotes and have shorter tails. These creatures can best be recognized by their tubes that have fused together and meet in the middle of the head.

The Oxysalpincidia are the most widespread of the Diplaulotes and contain a myriad of species ranging from small and slender hexapods to titanic bipedal behemoths. Indeed, some of the largest terrestrial animals alive and consequently, the largest terrestrial Trapezostomes to ever exist are Oxysalpincidians.

Exolophodontia

The final of the three major branches of Liomedactylae are the Exolophodontia. These creatures are perhaps the most un-Trapezostome like Trapezostomes ever. In fact, for the first decade or so after explorations on Eryobis began, the Exolophodonts were not even considered to be Trapezostomes because they often have strongly reduced- or completely lack trapeziums.

Exolophodonts gain their name from their teeth which are, peculiar to say the least.

Liomedactyls all started out with a full set of teeth on their maxilla, dentary and a row of palatine teeth. At some point in their evolution, the ancestors of Exolophodonts suffered a mutation that caused their maxillary teeth to turn outwards and would end up forming a "crest" of teeth that stuck out of the mouth.

For most Anisospondyls this would be disadvantageous in several ways, but since these Liomedactyls still had fully functional palatine teeth, they were able to compensate.

It is likely that individuals with these odd teeth were selected for because it likely showed their fitness and ability to live with a feature that would seem like a hindrance. Soon these teeth would be developed into all kinds of shapes and sizes.

Some of the most basal Exolophodonts are the Ankylotalariidae, a family of arboreal omnivores with strangely shaped ankle bones and prehensile tails. Typical of many basal Exolophodonts, their toothy crests give their face an appearance akin to a leiomano or macuahuitl. Despite this seemingly fearsome look, the teeth are brittle and are exclusively meant for display.

The Choeromelidae are another quite basal family of Exolophodonts, although these creatures have more specialized maxillary teeth than other basal members. The tusks of Choeromelids are strong and are used for digging up food, scratching the bark of trees and for combat. Curisouly, these critters have some of the most well retained trapeziums of any Exolophodontian family.

The family that the order derives it name from, the Exolophodontidae, are a family of medium to very large sized herbivores native to the Rubiëran archipelago. These pachyderms have spade like crest teeth that are often larger on the visendal side than on the caecal side. They are the largest land animals in Rubiëra and they permanently hold their caecal limbs off the ground. These are used for digging, collecting food and fighting.

In a curious case of convergent evolution, a family of Exolophodonts evolved a very similar body shape and lifestyle to the Cryptognaths known as Kadrians. The aptly named Pseudokadridae are also a family of long, slender legged herbivores that, like their namesakes, walk quadrupedally while having reduced one pair of their front limbs. Unlike actual Kadrians whose non walking front limbs have turned into defensive weaponry, the Pseudokadrids use theirs to hold and transport food, other materials and offspring. The tooth crests of Pseuodkadrians can vary wildly between different genera and even species, but they are generally quite sturdy and are often used for both intraspecific combat and defense if necessary. Their spiracular tubes are also often quite elaborate and brightly colored, especially in the males and are mostly used for display.

Pseudokadrids are also one of the very few members of a group called the Choritrapezioidea that are found outside the continent of Miesjeta. Most other members of this group can be in Miesjeta, with the subcontinent called Lotharca being especially rich in their diversity.

One of the most charismatic families of this group are the carnivorous Hemerosmilids. These predators are best known for having reduced all their maxillary teeth except for one, which they turned into a large blade shaped tusk with serrated edges. With this, they are the second family of Liomedactyls to evolve into sabertoothed carnivores along side the Diplaulote Machairoplatids. They are not closely related at all however and evolved on opposite sides of the world. Hemerosmilids are also known for their peculiarly shaped headgear that often resemble caricatured wings. Because of this, some explorers call them "cats of Hermes".

Perhaps the most widespread family of Choritrapeziods are the Polemotheriidae. These squat, pig to rhino sized herbivores can be found all over Miesjeta as well as some islands surrounding the continent. Like the Hemerosmilids, these creatures have also greatly reduced their number of maxillary teeth in favor of a few, but very large tusks. These are used for all kinds of daily activities like digging, stripping vegetation, combat and breaking through ice.

When one observes the locations of where terrestrial Trapezostomes can found in Eryobis, it becomes noticeable how the majority of their more basal taxa can be found in Rubiëra.

Rubiëra ofcourse, is a massive archipelago that consists of the remnants of highlands of a sunken continent that was once much larger. Based on its unique flora and fauna, researchers think that Rubiëra has been more or less isolated from the rest of Eryobis since the World Scarring occurred.

Because of this Trapezostomes were able to evolve and diversify unhindered by the Cryptognaths that dominated all other continents.

Back in the early Afthonozoic, Rubiëra as well as Lotharca and Augadrië and possibly parts of Wyndraë were united in a much larger continent dubbed Magna-Rubiëra. It is likely that Liomedactyls used the breaking up of this paleocontinent to spread across the world.

Exolophodonts and Austroglires hitched a ride on Lotharca to spread to the rest of Miesjeta and the Diplaulotes seem to have evolved in Augadrian Tlèëa after the breakup of Magna-Rubiëra. Boreoglires likewise used Augadrië and Wyndraë to spread to the rest of Tlèëa, Guralta and Lachoba.

Currently, the only continent without any terrestrial Trapezostomes is Hatèmica. This continent was likely already isolated from all others by the time Liomedactyls spread out from Rubiëra.

Hatèmica however seems to be on a collision course with Guralta, is moving exceptionally fast for a continent and is likely to make contact within the next 20 milion years. So its apparent lack of Trapezostomes is destined to come to an end.